|

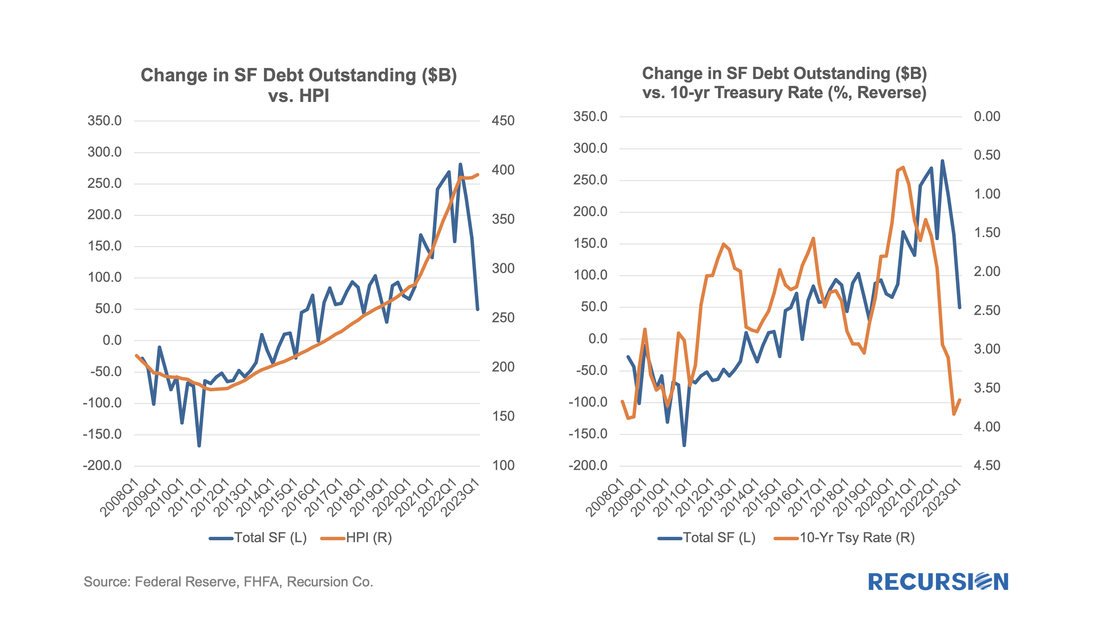

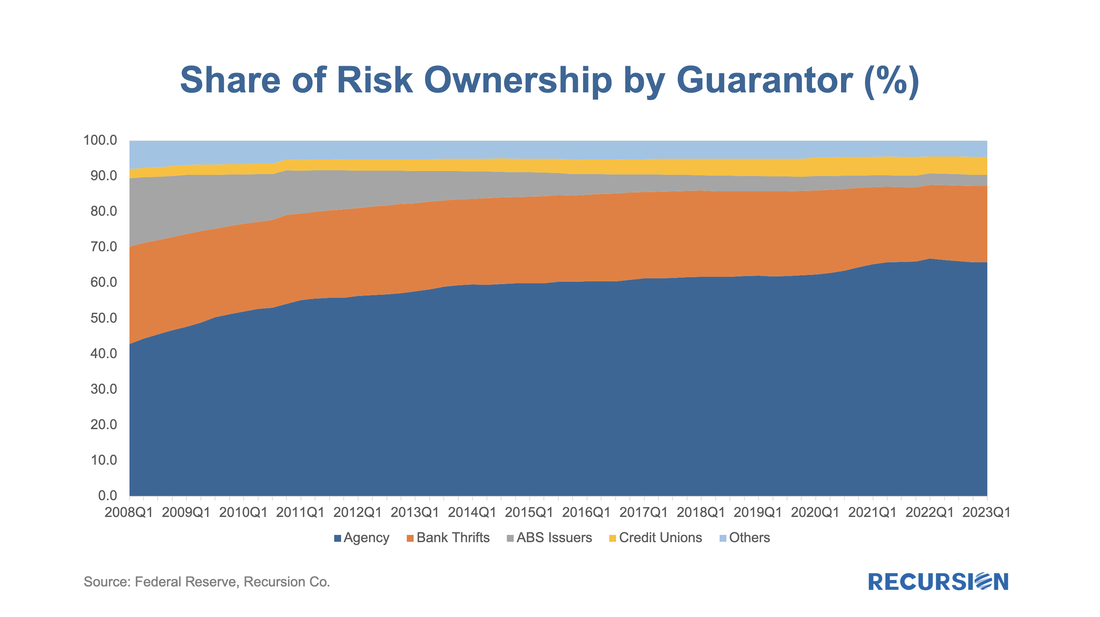

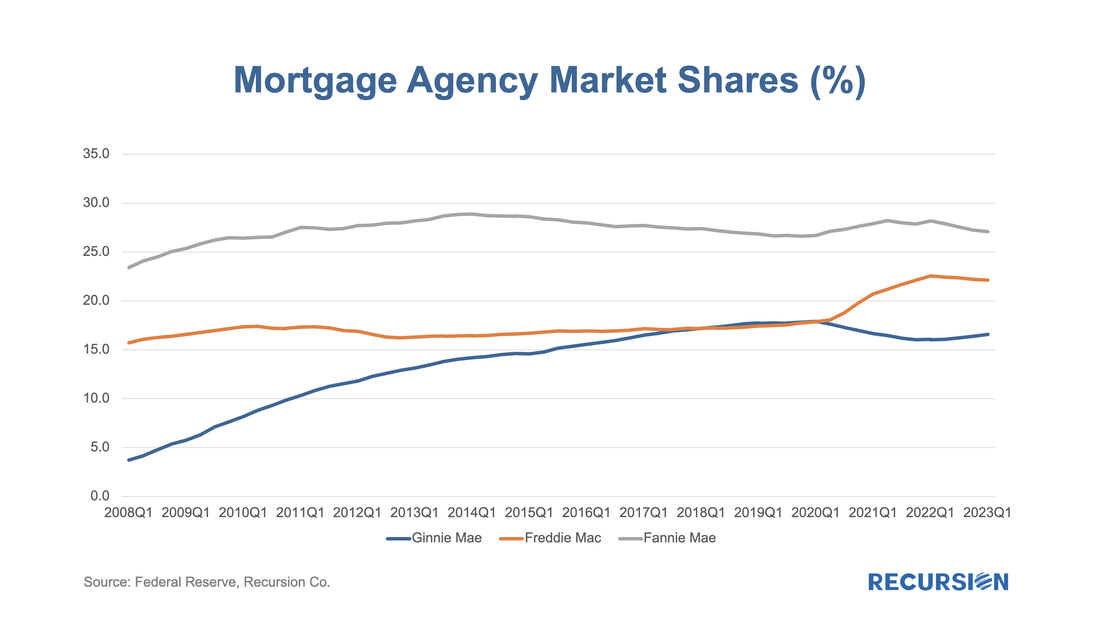

Overview The release of the Financial Accounts of the United States (also known as the Z.1[1]) is always an opportunity to learn about important structural changes in the mortgage market. This is particularly the case in our current environment of high home prices and borrowing costs which we call “mortgage winter”. In this note, we focus on the breakdown on the ownership of risk for single family mortgages. This is not the share of ownership of MBS; it is who bears the credit risk for the loans. Unsurprisingly, the growth in single-family mortgage credit outstanding in Q1 grew by the smallest amount in almost 7 years in the first quarter of 2023: The correlation between the HPI and change in outstanding SF mortgage debt over the period 2018Q2 and 2023Q1 is a robust 0.88, compared to 0.40 vs. the 10-year Treasury Yield (0.28 vs. 30-year mortgage rate). The regime shift towards “Mortgage Winter” can be clearly seen starting in the second half of 2022 when the growth in mortgage debt decoupled with HPI and instead fell as long-term interest rates spiked higher. Besides the macro picture, a great number of take-aways can be found by digging into the details in this dataset. To reiterate, this is ownership of credit risk in single-family mortgage loans. Trend Analysis 2008-2011 The single biggest share of holdings of risk is taken by the mortgage agencies. This share surged from 43% in 2008 to 55% in 2011 as the PLS market collapsed. The category “ABS Issuers” captures the securitized part of the PLS market, and the share fell from 19% to 12% over this period. The remainder of PLS would have been held in the form of loans held on balance sheets which are not tracked as a separate item in this data. 2020-2022 Notable trend changes are next seen with the onset of the pandemic in Q1 2020. At this time, banks became concerned about the corresponding increase in uncertainty regarding credit risk for mortgages; consequently, their investment preferences shifted from mortgage loans to MBS. The Bank segment fell by 3% from Q4 2019 to 20.7% in Q1 2022, while the Agency share jumped by 4.6% over the same period to 66.9%, the first and only quarter that the figure has been over 2/3 since the Global Financial Crisis. After that time, pandemic fears eased and the changes in shares partially reverted to pre-Covid levels. The bank and agency shares at the end of 2022 stood at 21.5% and 65.8%, respectively. Mortgage Winter Living up to its name, shares in the holdings of single-family mortgage risk broken down by major categories barely budged in Q1 2023 from the prior quarter. That’s not to say that nothing can be expected to change for an extended period, but rather that the changes are likely to be policy and regulatory, rather than economic, in nature. Housing Policy in Mortgage Winter The high-interest rates and house prices associated with mortgage winter have impinged mortgage activity and look set to act as drags on the market for some time to come. This is not to say that the status quo will continue. The US single-family housing finance market amounts to over $13 trillion of household liabilities, and untold billions in income to mortgage bankers, securitizers, insurers, builders, brokers, appraisers, and others in various support sectors. On the public sector side, housing policy is crucial to both financial stability and wealth equality. If the industry isn’t riding a wave of growth, the natural tendency will be for these powerful interests to attempt to tilt the playing field in their direction to support their own financial and policy interests. We are already seeing the first stages of this adjustment. The volatility in Q1 associated with bank deposit outflows has settled down, but these events have brought to light vulnerabilities in the financial system that have caught the attention of regulators. The market is now focused on such matters as the “Basel III Endgame” [2] and changes in the treatment of large regional banks[3] and more. A full discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this note, but prospects are growing for a tightening of credit conditions for mortgage borrowers in the banking system, and for reduced bank demand for mortgage loans on their balance sheets. This development does not, however, naturally lead to an overall decline in credit availability, but more likely the continuation of the strong trend we saw in Q1 2023: a surge in the nonbank share of mortgage originations[4]. But there are also bigger picture issues. A decade ago, the housing policy debate was dominated by a single issue: the organization of the mortgage finance system. Every housing organization and notable analyst put out their ideas for how the system should be reformed. The assumption was that conservatorship was a temporary condition, that the GSEs would evolve into some other state, like it had been before the crisis, or something else. Instead, the improbable happened: nothing. This September will mark the 15th anniversary of the GSEs being taken into conservatorship. The conversation on this issue has quieted down over the last decade, by a lot. That doesn’t mean it’s gone. The stalling out of industry activity will be an incentive to revive this debate, particularly as the 2024 Presidential election is just 15 months away. We cannot predict the outcome of all this, but it’s worth pointing out that an important set of statistics to watch in this regard is through the market shares of the three Agencies: Going back to the GFC, it’s very important to remember the importance of the Government sector, particularly FHA, in stabilizing the mortgage system as the PLS market evaporated. This has been forgotten in many quarters, but it may well be the most successful housing policy initiative to come out of the GFC. But more recently, what stands out is the surge in the GSE share with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in Q1 2020. There has been a lot of discussion about this topic, but a plausible explanation is that record low borrowing costs induced holders of FHA loans to refinance into conventional mortgages with their favorable fee structures . This was supported by the lower LTVs that these borrowers experienced from rising home prices. It’s interesting to note that this trend has reversed slightly in the last few quarters. It may well be that this is due to specific policy decisions in the Government mortgage space, but this is not clear. It will be very interesting to watch how this trend develops in the Q2 data since, as we already noted, the slew of fee changes that occurred in both the Government and conforming spaces in recent months seem to be tilting the playing field back toward the GSEs[5]. We will see. Finally, there is the Fannie/Freddie share, sometimes called the “traditional” share. Historically, this was 60/40. This is where it stood throughout 2008. It rose to a peak of 64 in 2013-14. This rise was a source of concern to policymakers worried about the market power of the senior GSE. In 2012, FHFA released its plan calling for the creation of a new Unified Mortgage-Backed Security (UMBS). This was launched in 2019[6]. Almost immediately after the announcement the share began to narrow, and it returned to 60 in 2019 and stayed there until the onset of the pandemic the following year when it started to take a sharp dive. The reason for this next stage of narrowing, we believe, is not the UMBS but rather our finding that the Federal Reserve’s “QE” program of asset purchases disproportionately involved a larger share of Freddie Mac securities than their overall market rate[7]. The share fell to 55 in Q2 2022 and stayed there for four consecutive quarters. What now? FHFA Director Thompson has indicated that preparing the GSEs for life after conservatorship is an important goal of the Agency[8]. This involves two main areas for consideration: 1). The Enterprises need to be well-capitalized. Capital needs to be sufficient for them to operate in a highly distressed economic environment without taxpayer support. The level of necessary capital to achieve this result is viewed as $300 billion. At present, their combined capital is about $100 billion so we are not there yet. 2). Out of conservatorship does not mean unregulated. A new regulatory framework needs to be developed to deal with the safety and soundness of the GSEs and also their Mission requirements once they are not in conservatorship. There are many complex and politically charged issues to be resolved for this to occur. Other options remain very much open. Our main take-away from the Agency share data is that the two GSEs look more and more alike. An important theme at Recursion is that we are an analytical shop and not an advocacy firm. But sometimes, old opinions are hard to keep down[9]. [1] https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/

[2]https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/what-is-basel-iii-endgame-why-are-banks-worked-up-about-it-2023-07-24/ [3] https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1648 [4] https://agency.recursionco.com/cgi/display.cgi?id=365&rs=&tbl=4 [5] https://www.recursionco.com/blog/tales-from-the-fee-skirmishes [6] https://www.fhfa.gov/PolicyProgramsResearch/Policy/Pages/Securitization-Infrastructure.aspx [7] https://www.recursionco.com/blog/the-fannie-freddie-share-revisited [8]https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/Written-Testimony-of-Director-Thompson-Before-the-HFS-Committee_5232023.aspx [9]https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2018-01-15/a-bad-start-on-reforming-fannie-and-freddie |

Archives

July 2024

Tags

All

|

RECURSION |

|

Copyright © 2022 Recursion, Co. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed