|

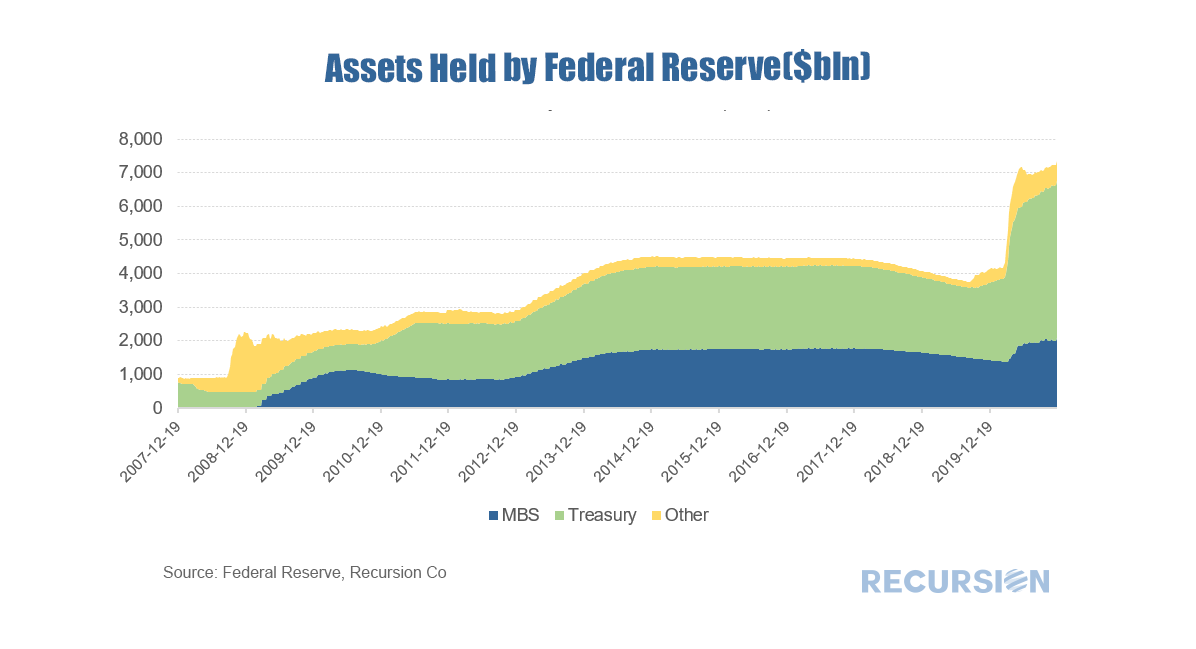

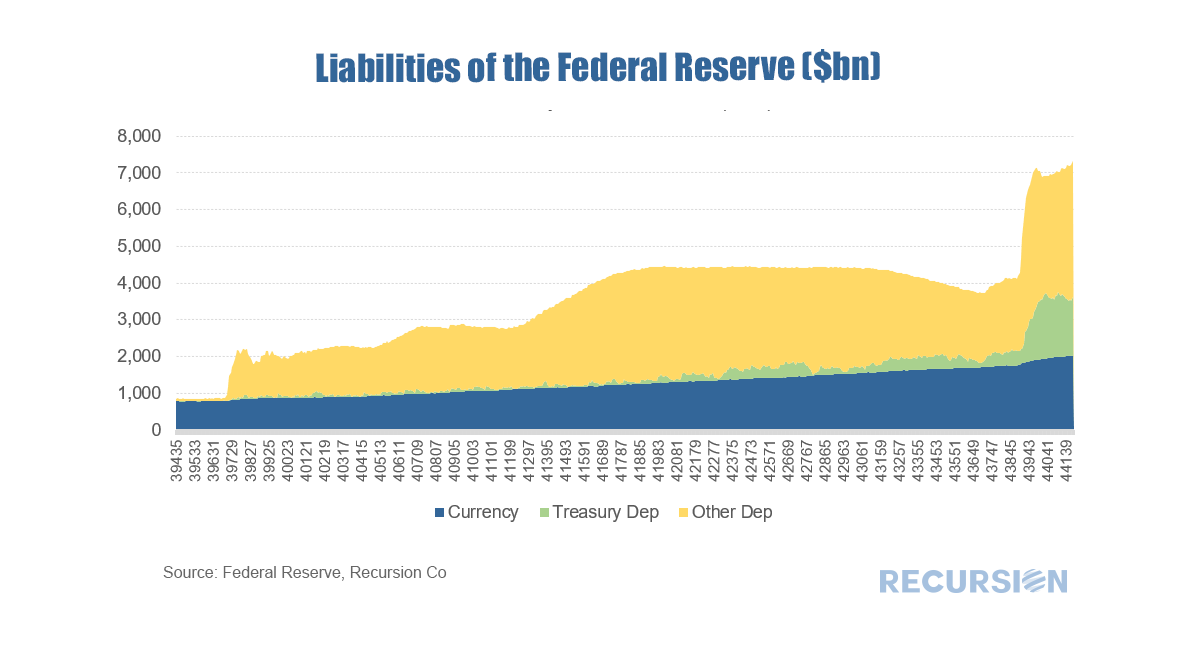

The role of the Federal Reserve in the mortgage market is an ongoing theme in this blog, dating back to the early days of the Covid-19 crisis[1]. Besides the level of short-term rates, when we think about the Fed, we consider its direct intervention through the outright purchases of MBS. A common view of this “QE” policy can be seen in charts such as: Like any bank, the Fed holds securities and loans on the asset side of its balance sheet. The securities are Treasuries and MBS, and loans are a myriad of direct lending programs including the discount window, and swaps to foreign central banks. The idea is that when the Fed adds to its holdings of MBS, direct downward pressure is placed on the mortgage rates available to borrowers. There is, of course, a flip side to the chart above and that is the liability view of the central bank’s balance sheet. In this way, the Fed is also somewhat different from commercial banks. Yes, they take deposits, but not from consumers. In terms of liabilities, the debt they issue is currency. In terms of equity, many people are surprised to hear that they do issue that, but it doesn’t yet trade on the Nasdaq. Instead, it’s interesting to note that member banks must hold shares of their local Federal Reserve bank on their balance sheet[2]. So here is the same picture looked at from the other side: This is less familiar. One point that stands out is that the green shaded area, largely commercial bank deposits at the Fed, jumped in 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis, and again this year with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. The Fed only started paying interest on these deposits in 2008, providing a way for banks to earn some return on the surge of deposits risk averse consumers and firms sent to the banks. What is notable here is the orange shaded area: the deposits of the US Treasury at the central bank. These were negligible before the Global Financial Crisis, grew modestly during the ensuing recovery, and then shot up during the Covid-19 Crisis. The natural question here is: What’s up with that? Treasury is not a bank, so it needs one to pay coupons on debt and for stuff the Government needs to do its job. Historically, the Treasury has managed its account to keep it small through active cash management, such as issuing short-term bills to generate cash to avoid the embarrassment of overdrawing its account with the Fed. Essentially, and importantly, these bills tend to draw money held by investors out of their deposits in the banking system. This started to change in the mid 2010’s, when Treasury allowed its balances at the central bank to rise. This happened after the government shutdown of 2013, when it became clear that the solvency of the Treasury was being used as a strategy to influence budget negotiations. So, the optimal balance changed from close to zero to something greater than that as a risk-mitigating measure. The government can remain solvent for longer. Finally, while this is interesting, what does this have to do with the mortgage market? Well, as the Treasury’s account grows, money is drawn out of reserves held at banks. Consequently, the banks have less money to lend or to allocate to long-term assets such as MBS. So the surge in Treasury balances is working somewhat against the Fed’s efforts to push down on long-term rates. So, a great question for 2021 for mortgage market participants is what will Janet Yellin do with all that cash she has available deposited with her former employer, assuming her nomination is approved by the Senate? Stay tuned. |

Archives

July 2024

Tags

All

|

RECURSION |

|

Copyright © 2022 Recursion, Co. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed