|

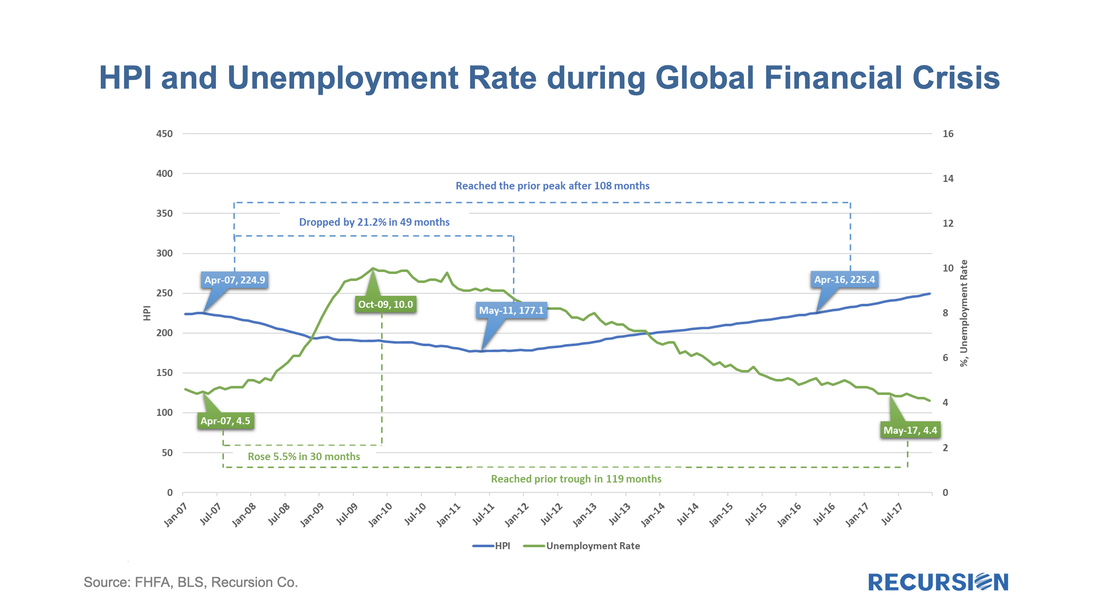

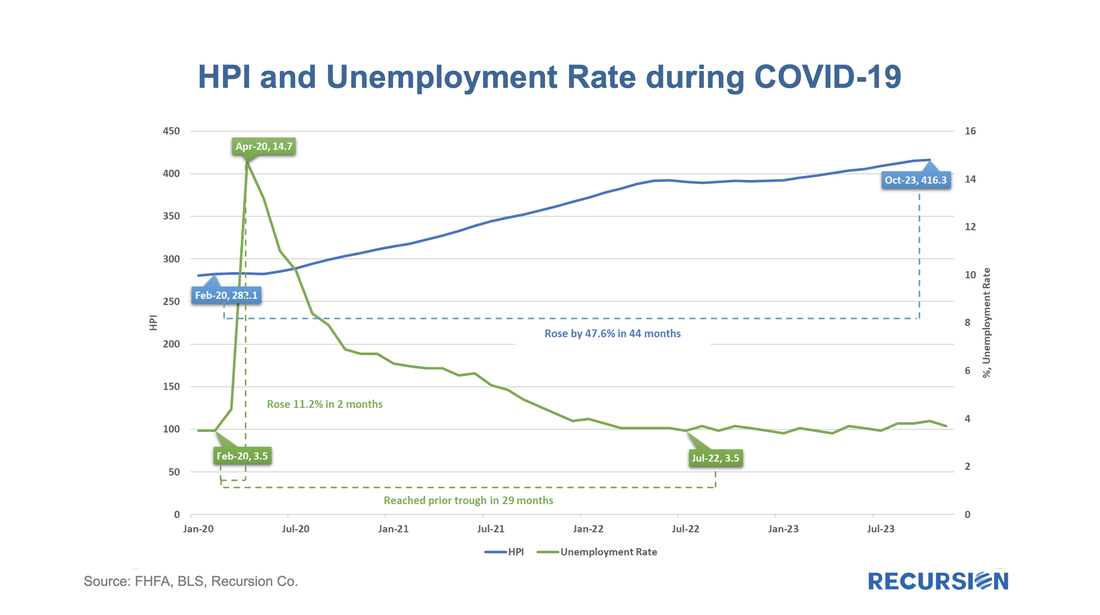

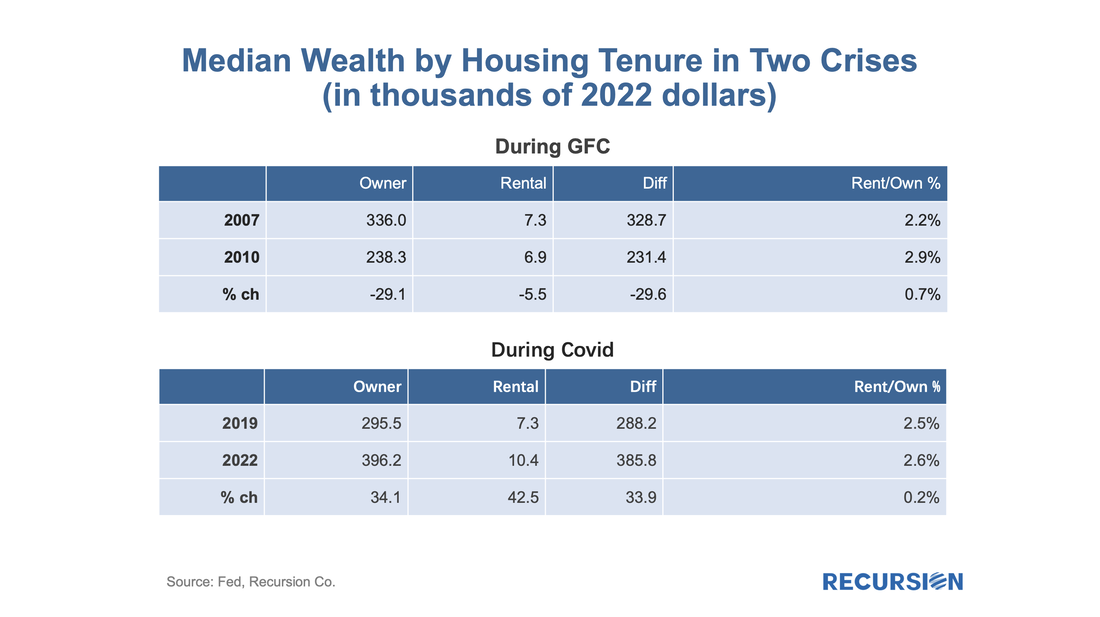

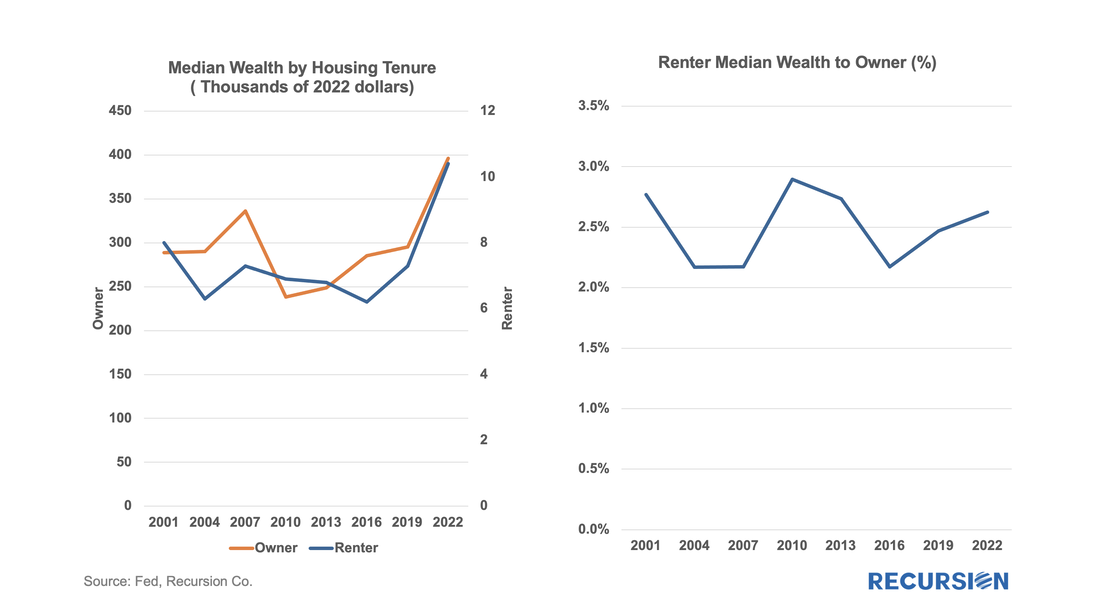

We kicked off 2024 with a post looking at the sensitivity of low-income borrowers to a slowdown in the economy[1]. We saw continued solid correlations between labor market conditions and jobless claims, particularly for low-income borrowers. At present, these all remain near historically low levels. However, we also saw growing distress in some categories of borrowers with modified loans. It seems that policymakers are going to great lengths to keep homeowners out of foreclosure. This effort falls directly out of the experience of the Global Financial Crisis, where six million households lost their homes while only one-quarter of these regained homeowner status afterwards[2]. This led to a persistent period of slow growth in the decade following the crisis, a situation that policymakers have become determined to avoid. Consequently, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, policymakers were prepared with a policy of forbearance where households who were impacted by the disease were allowed to defer payments until their economic situation improved. The policy was extraordinarily effective. Unemployment and House Prices in Two Crises During the GFC, the unemployment rate rose by 5.5% to 10%, while house prices plunged by over 20%. It took nearly a decade for the unemployment rate to reach pre-crisis levels. During Covid, the unemployment rate soared by over 11% to 14.7% in only two months. This time, however, it dropped to its pre-crisis level in just 29 months, four times faster than the experience of the GFC. The house price picture was completely different with virtually no drop in prices experienced at all and a cumulative gain posted in the subsequent 3½ year period nearing 50%. While there are many other differences between the GFC and COVID crises, it would be difficult to argue that forbearance was not a significant contributor to the relatively favorable housing and economic outcomes experienced in the latter crisis. This leaves us, however, with another problem, namely the lack of affordability and persistent wealth inequality. To discuss these issues, we turn to a different dataset, the Federal Reserve’s triennial Survey of Current Finances (SCF)[3]. According to the Fed, “The Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) is a triennial cross-sectional survey of U.S. families. The survey data include information on families’ balance sheets, pensions, income, and demographic characteristics.” It is a source widely used by researchers to discuss paramount issues in public policy. A fine example is recent work by Fed researchers regarding how greater wealth uncertainty is associated with changes in racial inequality[4]. For our purposes, the most useful indicator provided in this report is the breakdown in wealth by housing tenure: namely homeowners vs. renters. By a fortuitous stroke, the most recent survey came out last September for 2022, so we have a clear view of developments since just before Covid struck in 2019. Similarly, we have observations for 2007 and 2010, near the peak and trough of the cycle associated with the GFC: Once again, the differences between the two periods are striking. Wealth collapsed for homeowners during the GFC while it fell modestly for renters. With Covid, wealth in both categories soared. Remarkably, renter’s wealth gains outstripped those of owners in percentage terms during the pandemic. Interestingly, inequality declined in both periods as measured by the share of renter wealth relative to owners rose in both periods. Some useful perspectives on this topic can be gained by looking at longer-term trends. First, households who own their residences tend to have more volatile wealth profiles than renters. It is interesting to note that in most periods, the change in the wealth of renters tends to have the opposite sign of the change in owner wealth (the exceptions being 2001, 2007, and 2022). Consequently, the share of rental wealth relative to owner has been relatively consistent in the recent two decades. Second, timing matters. Most analysts accept the notion that housing is key to the generation of intergenerational wealth. But if you became a homeowner in 2007, your wealth declined sharply and did not exceed the prior peak for 15 years. That is a period that can’t be dismissed as short-term. Housing now is far more unaffordable than in 2007, so what can be done to generate wealth formation in the current situation? This is a complex question beyond our normal scope. However, a sharp drop in house prices seems unlikely barring a fierce recession. On the other hand, another 50% increase in house prices over the next several years appears unlikely as well. Recalling our “mortgage winter” theme, the solution seems to lie in the formulation of innovative programs to supply affordable housing to a broad population over an extended period as economic recovery lifts family income. Unlike traditional policies, these are likely to be place-based and require cooperation across all levels of government working with the private sector. Watching developments in this area will be key to monitoring the health of the mortgage market in 2024 and many years thereafter. [1]www.recursionco.com/blog/how-sensitive-are-fha-borrowers-to-a-weakening-economy

[2]https://www.nber.org/papers/w25403 [3]https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scfindex.htm [4]https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/greater-wealth-greater-uncertainty-changes-in-racial-inequality-in-the-survey-of-consumer-finances-20231018.html |

Archives

July 2024

Tags

All

|

RECURSION |

|

Copyright © 2022 Recursion, Co. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed