|

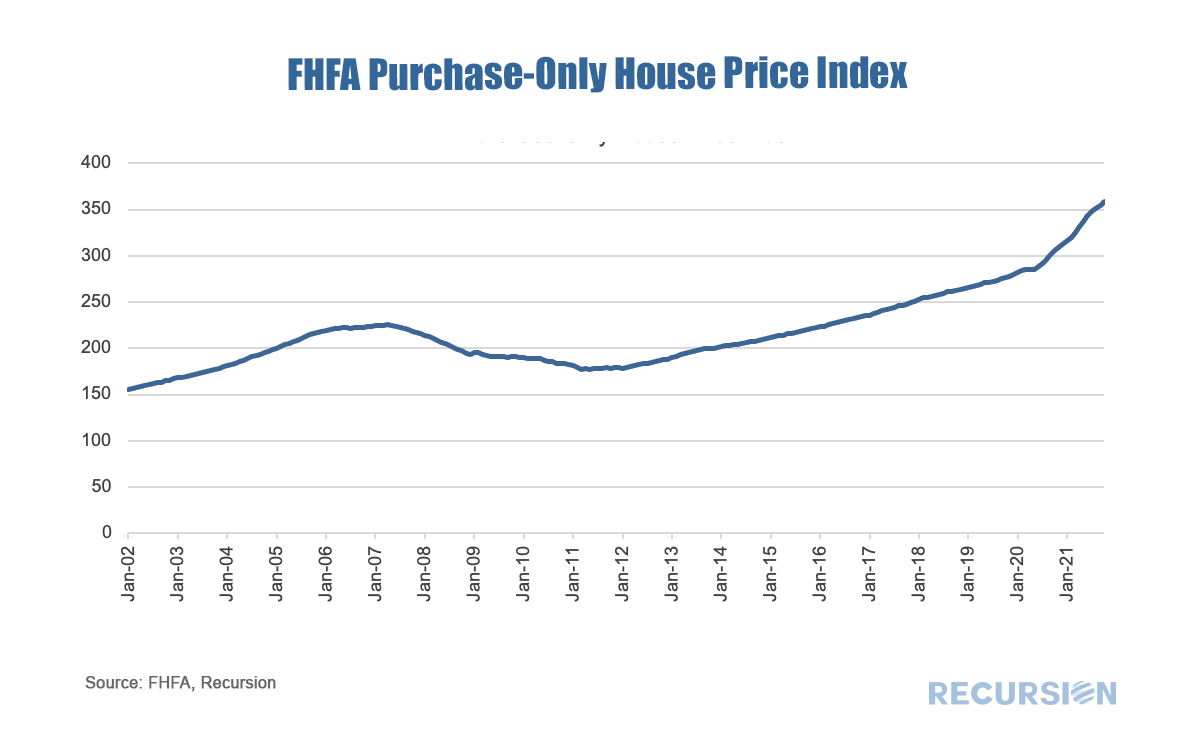

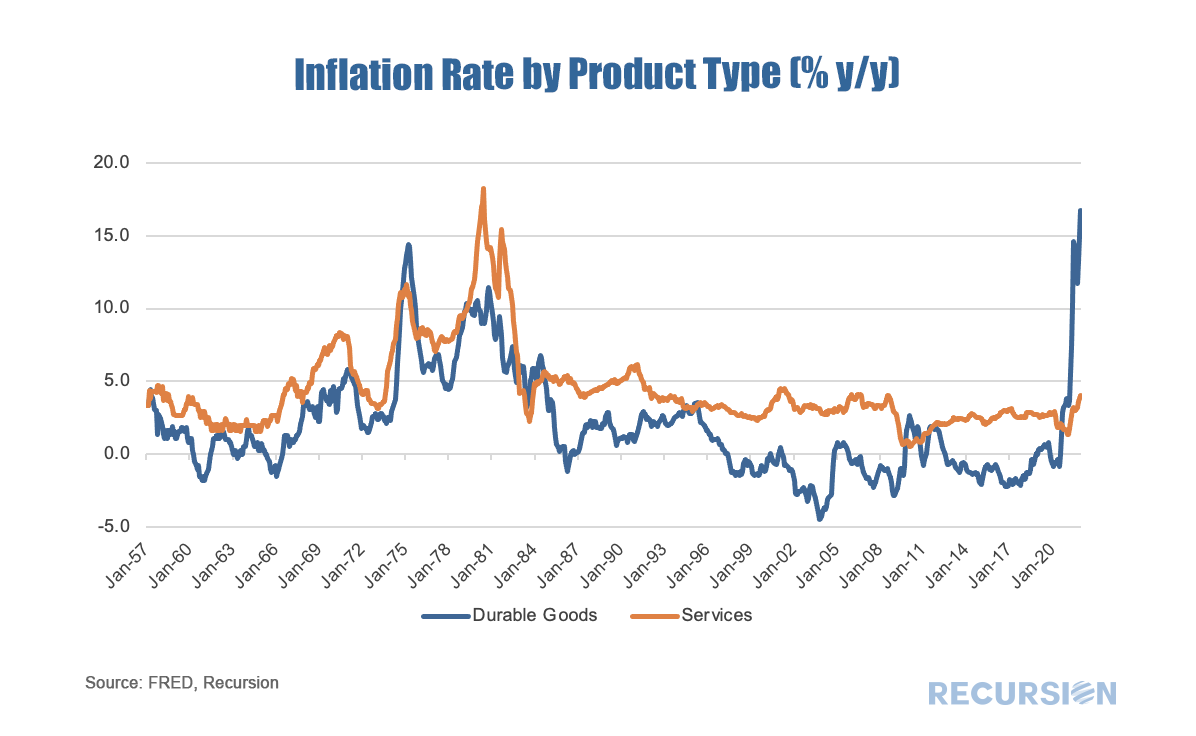

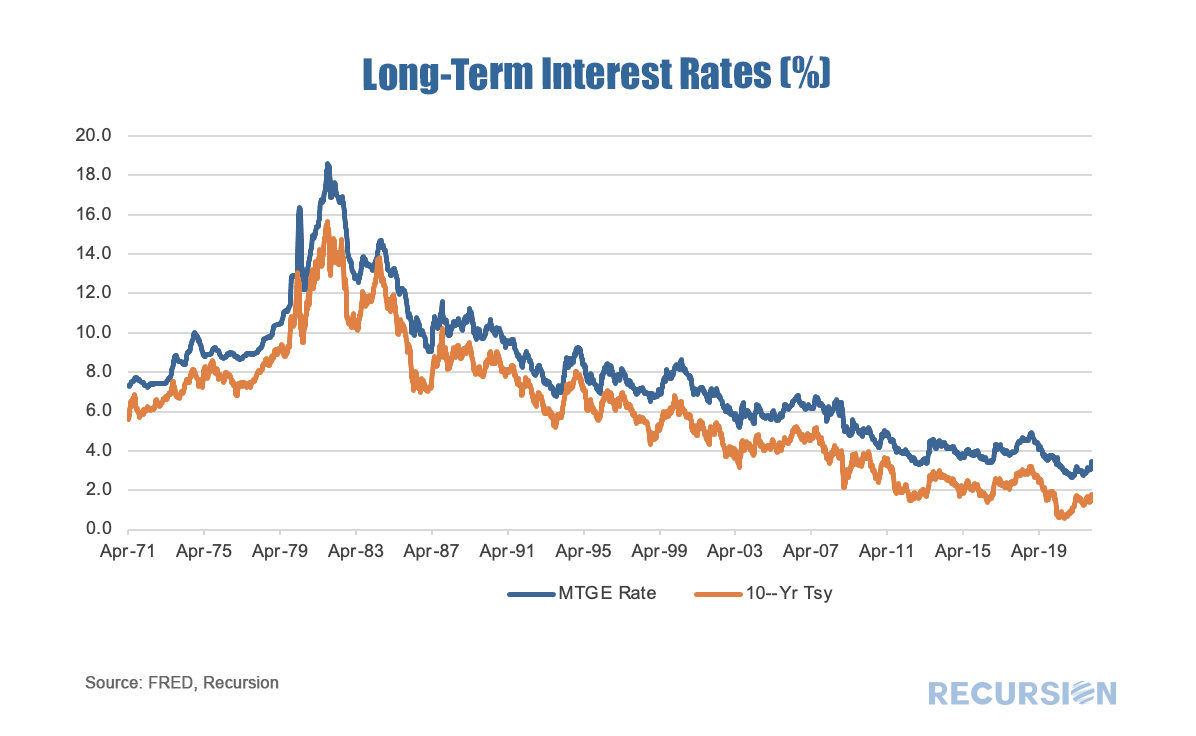

An ongoing theme of these posts has been the way that the Covid-19 pandemic and the policy response it has engendered have served to upend traditional relationships in the system of housing and housing finance. During the Global Financial Crisis, the unemployment rate surged to 10%, and housing prices collapsed by 35% causing widespread devastation in global financial markets. Shortly after the onset of the health crisis, the unemployment rate shot up close to 10% again, but this time, house prices soared, rising over 25% from May 2020 to October 2021. The difference is striking, and the result both of differences in the policy reaction, as well as the more fundamental reason that the GFC was a financial shock while Covid is physical in nature. It’s changing fundamental relationships between living and work. There is no reason to believe that other relationships won’t be impacted in similarly striking ways. The financial news is dominated by talk of surging inflation and the Fed’s reaction to it. Comparisons are made with the inflation episode of the 1970s and 1980s. But just as the Covid crisis is very different from the GFC, there are significant differences between the current episode and that period fifty years ago. A very simple framework for thinking about inflation is “cost-push” vs “demand-pull”. In the first case, increases in input costs such as employee costs and commodity prices are passed through to end users. In the second, rising incomes can cause aggregate demand to exceed supply. The distinction is more evident now than it ever has been before. In the 1980’s goods and services prices moved more or less in synch and that is not the case at all right now. Services prices (demand pull) are mostly the result of movements in wages while those for durable goods (cost-push) are set in product markets. Once again it seems it is the physical nature of the Covid shock that drives the distinction at present. Demand is high, but more for physical goods like cars and video games than for services like restaurants and vacation travel. Moreover, the virus makes workers sick, leading to disruptions in supply chains that result in sharp price increases for certain products. The outcome for this, of course, has profound implications for the housing and mortgage markets. Mortgages are priced off a spread to longer-dated Treasuries. Nearly two years after the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, the unemployment rate and long-term interest rates have returned to near their pre-crisis levels. Are long-term interest rates poised to climb with inflation? It could be, but the issue that needs to be addressed is which sort of inflation you’re looking at. This poses a dilemma for monetary policymakers, as they peer into uncharted territory.

|

Archives

July 2024

Tags

All

|

RECURSION |

|

Copyright © 2022 Recursion, Co. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed