|

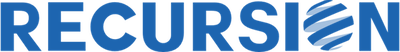

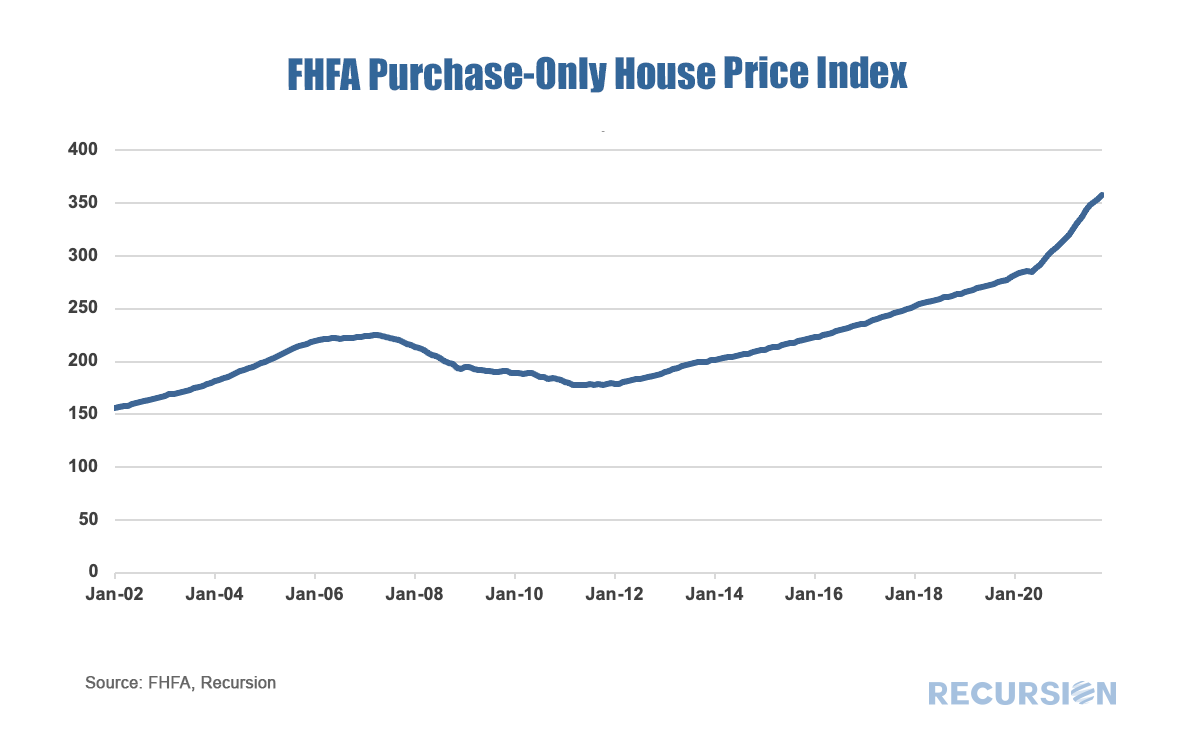

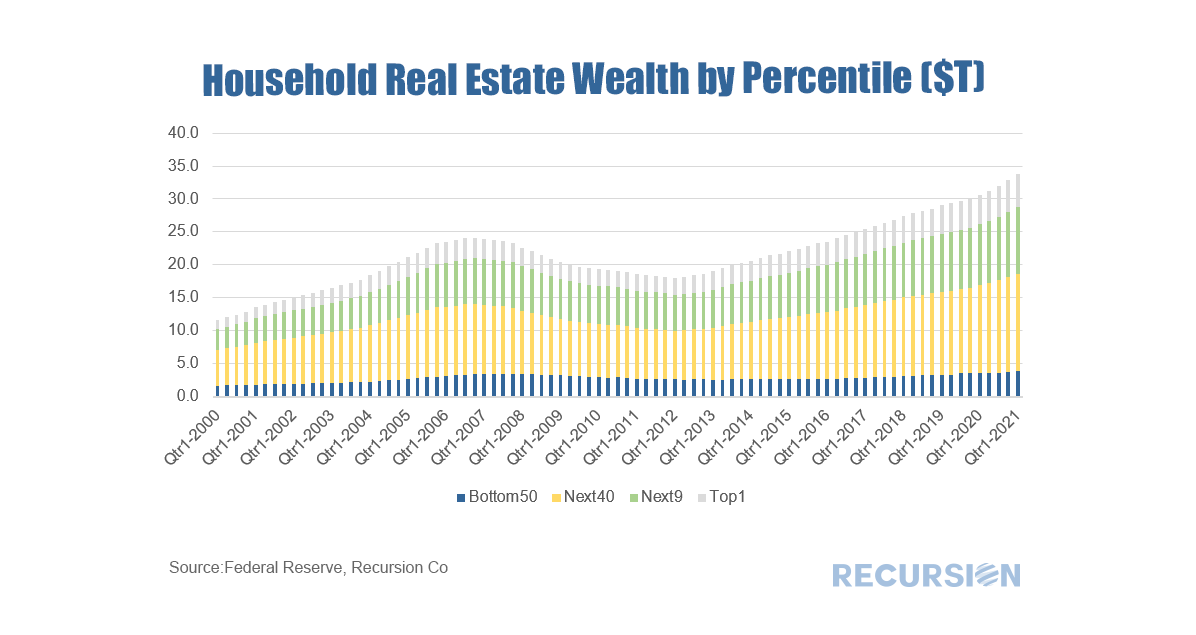

Once again, we look at the release of house price data with a sense of shock: Last week’s release of the April 2021 FHFA Purchase Only House Price Index showed a month/month increase of 1.76%, a record high. The yr/yr rise was 15.71%, also a record high. And this is from levels that were already record highs. The yr/yr increase in April towers over the 10.68% peak attained during the bubble period in September 2005. As this presaged the devastation experienced during the Global Financial Crisis, the question naturally arises as to whether a similar outcome is inevitable whenever a new downtrend commences. Regular readers of this blog will recognize that we do not provide forecasts, only data and tools. But a useful observation is that the sample size of national house price bubbles in the last 80 years in the US is one, so some caution about comparisons is called for. In any case, policymakers’ focus at the moment is directed towards inequality. This new focus creates analytical challenges because our macro data is focused primarily on growth rather than distribution. But efforts are underway to deepen our view of distribution and one that has been around for a while is the Federal Reserve Distributional Financial Accounts (DFA)[1]. The DFA is a rich data source with a wide breadth of information broken down by income, race and other characteristics. The Q1 2021 release came out a couple of weeks ago, which provides a picture of housing wealth broken down by percentile: The real estate wealth held by households has risen by about 87% from the trough obtained in Q1 2012. Household wealth is concentrated in the upper-middle class to the top 1%. Notably the share of real estate wealth held by the top 1% is about 28% greater than the bottom half. The shares have not changed materially since the onset of the pandemic, as real estate prices have risen sharply across most price points. The most important distributional impact from the pandemic, however, is clearly that between homeowners and nonhomeowners. According to the Department of Census[2], the homeownership rate of families with above median incomes was 79.4%, compared to 51.7% for those below that level for Q1 2021. Clearly, the run-up in house prices during the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated wealth inequality by income group. The detailed data for wealth distribution by decile comes from yet another data set, the Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF)[3]. The latest observation is for 2019, and the data at that point showed that the median family wealth for homebuyers of $255,000 more than 40 times the figure of $6,300 for those who do not own their residence. These considerations have led policymakers to shift their attention from safety and soundness to a more balanced approach including inequality. In addition to the QM rule, and restrictions on non-owner-occupied mortgages that can be delivered to the GSE’s, the policy toolkit is expanding rapidly to include such areas as block grants and loans to LMI borrowers. What does this have to do with huge data sets at micro loan-level? The analytic basis for assessing policy needs to adjust in accordance with changes in the policy focus. At Recursion we are striving to enhance the underwriting information contained in our loan datasets to include social, demographic and environmental factors from outside sources at a fine geographic level to attain these goals. Much more to come. |

Archives

July 2024

Tags

All

|

RECURSION |

|

Copyright © 2022 Recursion, Co. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed