|

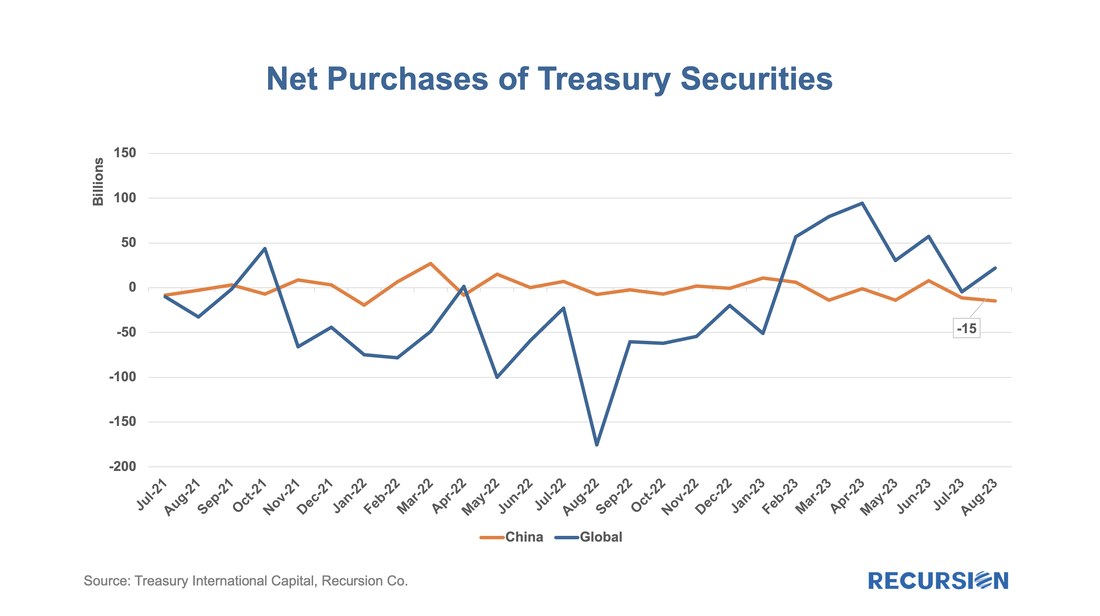

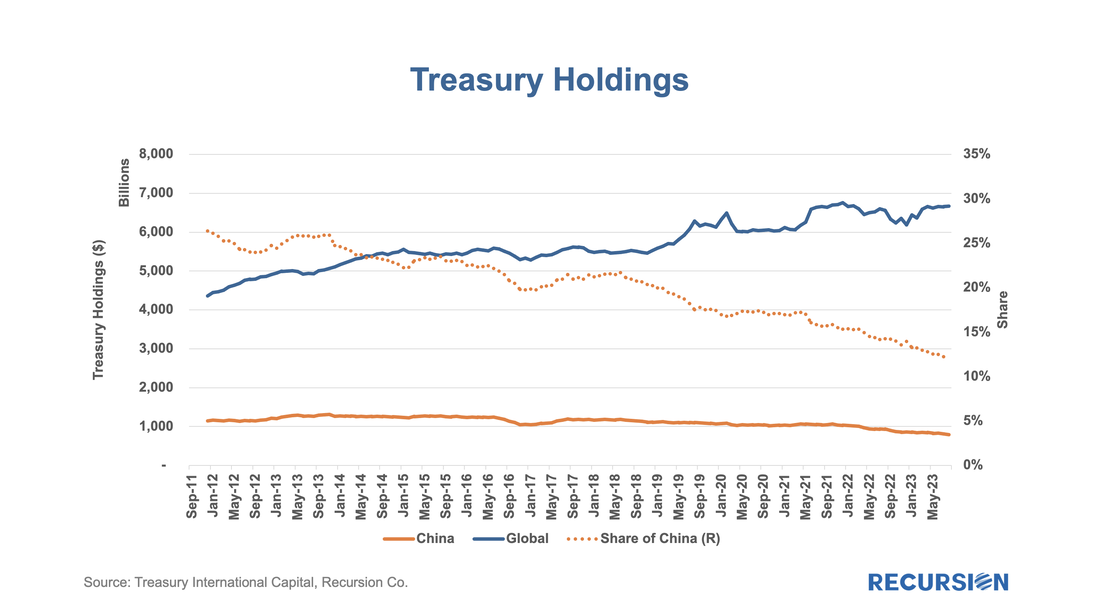

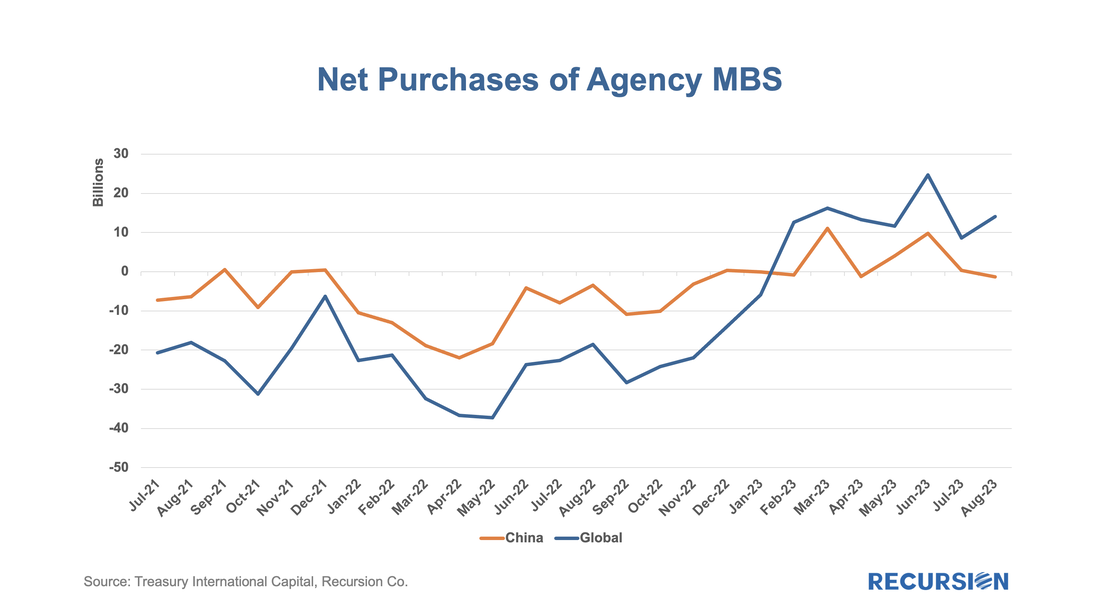

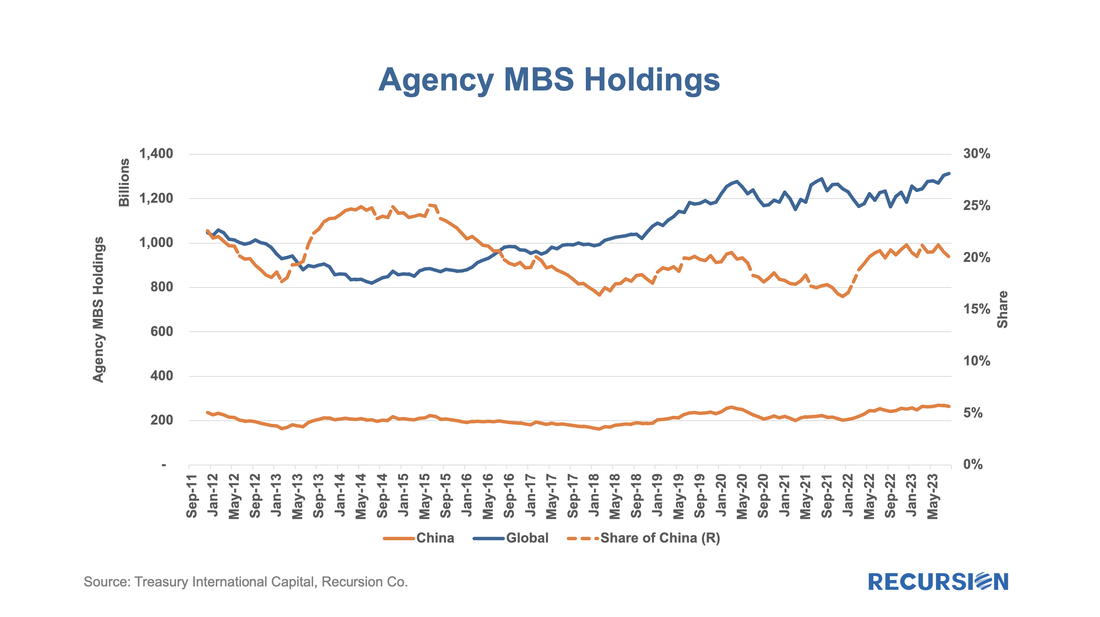

One of the key changes that has been underway in the policy environment over the last decade or so is the linking of economic and foreign policies. Trade policies in the form of tariffs or product bans have increasingly become part of the foreign policy toolkit. The most extreme case, of course, is the sanctions placed on Russia’s dollar assets by the US government following the invasion of Ukraine[1]. It’s natural to wonder if these developments could lead to changes in the foreign appetite for US financial assets. Recently, these concerns rose following reports of three consecutive months of declines in US Treasuries[2]. These are complex issues that matter to investors in US assets, so it’s worth looking into. Our Macro Analyzer provides a view into the main source of international financial flows, the Treasury International Capital (TIC) System[3]. Indeed, the data show sales of Treasury securities of almost $15 billion out of China in August, the biggest such figure since January 2022: A casual glance at the trend in this volatile time series does not appear particularly alarming. A somewhat more dramatic picture can be seen by looking at China’s holdings (as opposed to purchases) of Treasuries: These have declined by 37% over the past ten years, cutting their share of Treasury holdings by international investors in half over that period to 12%. The bulk of this decline came since early 2019, following the imposition of trade tariffs on China in late 2018[4]. Of course, correlation is not causality. The US fiscal deficit has widened dramatically in recent years, leading to growing concern about the asset across all classes of investors. How to distinguish? One way is to look at the demand for another long-dated fixed-income asset class, mortgage-backed securities. Here, the picture is a bit different: China has been a net purchaser of MBS in four of the last six months. The holdings picture is also distinct: Here, the picture is quite different, with China’s purchases of this asset rising since early 2022, with the share recently reaching 20% for the first time since 2016. Given that reduced supply is a key feature of “mortgage winter”, on net this gives a picture of a country adjusting its holdings according to the relative supply of the asset classes, rather than due to overt political considerations. As noted earlier, we are not global political experts, so it is useful to look at the reports of those who are. We do not often cite other blogs in these posts, but the outstanding expert in this field is Brad Setser at the Council of Foreign Relations, who writes the wonderful “Follow the Money”[4]. Anyone interested in this topic should follow him closely. For our purposes, we look at two points he frequently makes.

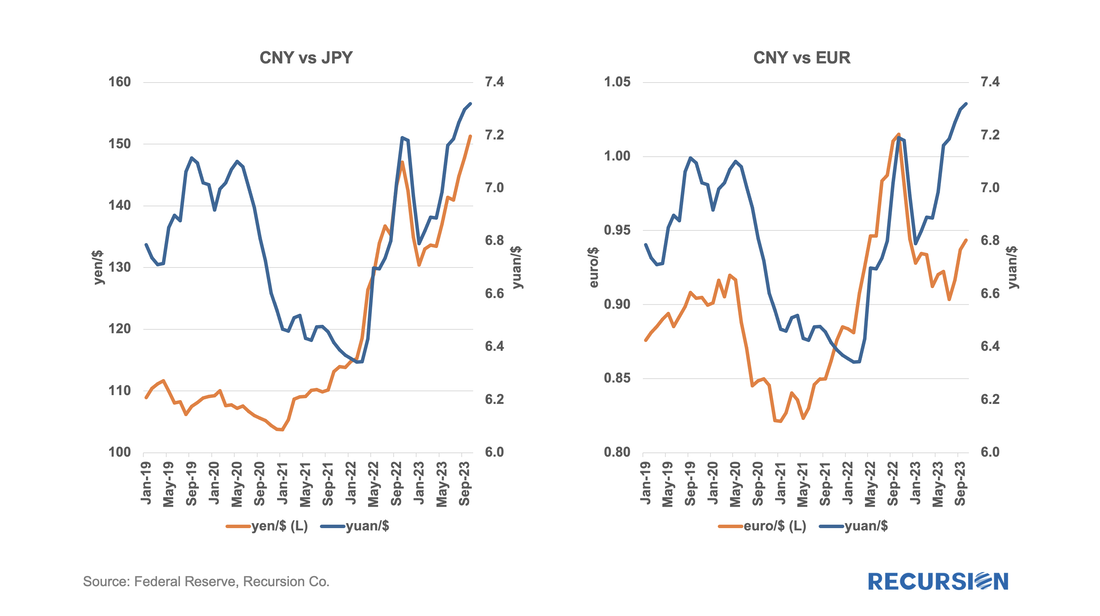

If China had been repatriating its dollar holdings back into yuan, it seems unlikely that the Chinese currency would have been weakening to the degree seen since early 2022, particularly given the tight correlation with the yen, as Japan has conducted no such trade. The euro has held up better than the yen this year, so some moves by China into the single currency can’t be ruled out, although this is far from assured. Given the uncertainty about the accuracy of bilateral capital flow data and uncertainty over financial market policies, the strongest statement that can be justified is that there is no concrete evidence of China exiting dollar markets for geopolitical reasons. Given the high and rising global tensions, it is impossible to forecast that such an event can’t happen in the future. [1] https://www.reuters.com/world/western-financial-sanctions-russia-2022-05-13/

[2] https://www.ft.com/content/4c2a39cb-6b15-4d41-b36e-c97afa1d8f66 [3] https://home.treasury.gov/data/treasury-international-capital-tic-system [4]https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/tariffs-trump-trade-war/#:~:text=The%20Trump%20administration%20imposed%20stage,into%20effect%20in%20May%202019. [5] https://www.cfr.org/blog/Setser |

Archives

July 2024

Tags

All

|

RECURSION |

|

Copyright © 2022 Recursion, Co. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed