|

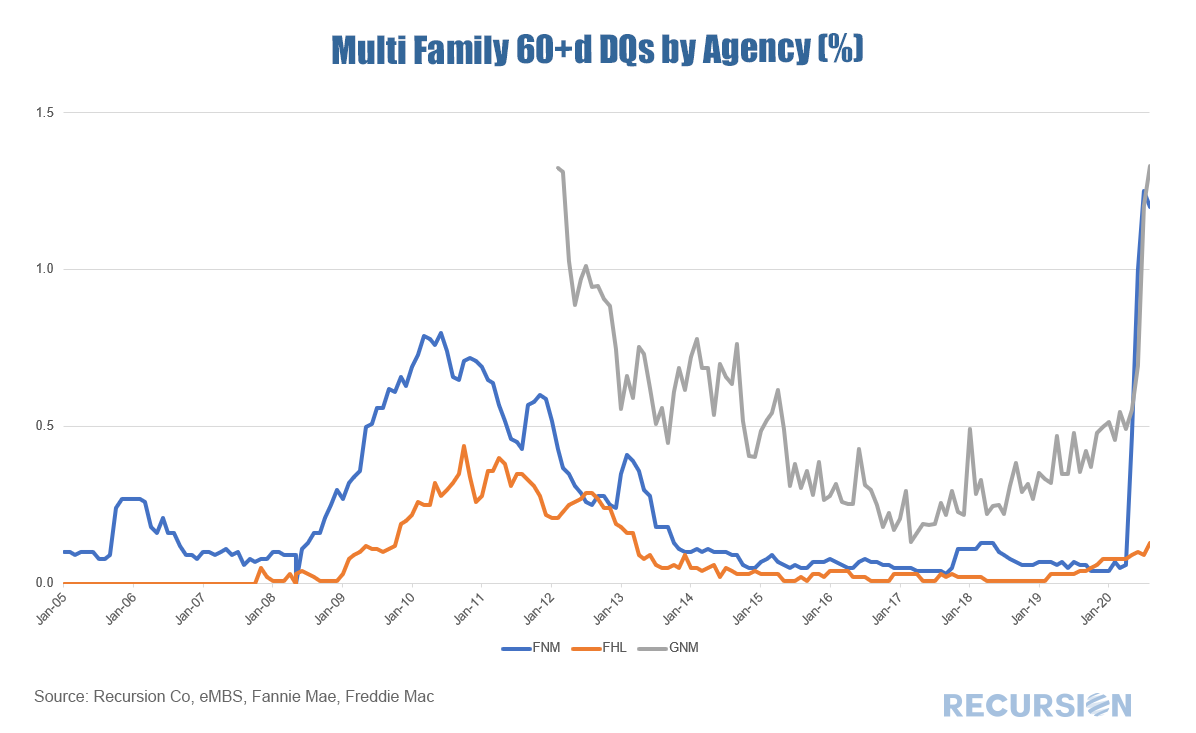

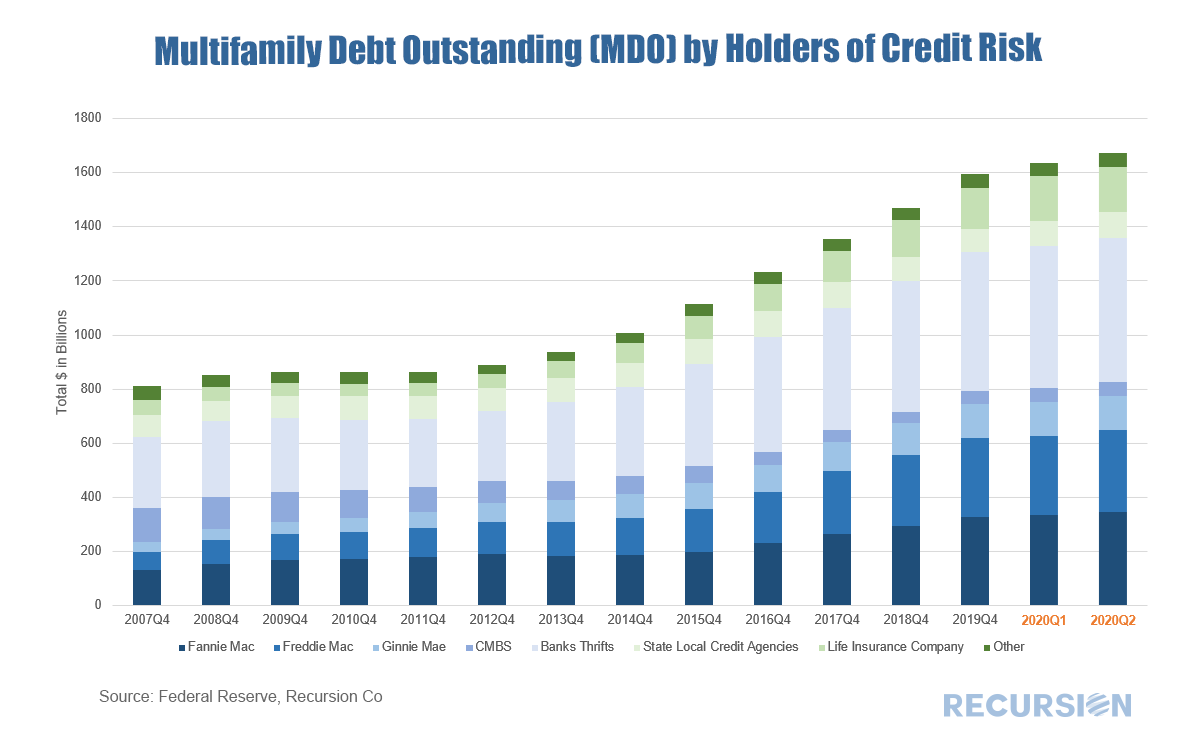

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of a dozen years ago was at its core a housing crisis. More specifically, it was a single-family mortgage crisis as imprudent lending led to a huge surge in home sales in a bubble that simply could not be sustained. The resulting collapse led to the biggest economic shock since the Great Depression. Until, perhaps, now. The other segment of residential housing, the rental market, skated through almost unscathed. While almost nine million people lost their jobs, including renters, millions of families lost homes and had to turn to rent, keeping the multifamily market afloat. This time is different. Low-wage service workers were the first to lose employment, and these are largely rental households. Of course, homeowners lost jobs as well, but this has not yet led to a surge in foreclosures due to forbearance programs. Renters have largely stayed put as well but the rental policy is a hodge-podge of federal and state and local rulemaking, so it is much more difficult to assess the status of the overall market. The key Federal statute in this regard was issued in September by the Centers for Disease Control which has banned evictions through the end of the year[1]. Housing policy is subordinate to health policy. A significant distinction between the single- and multi-family markets is that most loans in the rental market do not receive public support. Credit availability in this sector depends heavily on private assessments of the risk and reward of lending in this market. In order to assess the magnitude of the current shock in the multifamily space the chart below displays the 60+ day delinquency rates of the three housing agencies, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. The data for the two GSE’s comes from their monthly indicators while that for Ginnie comes from its pool-level disclosures. Interestingly, multifamily delinquencies for Fannie Mae and Ginnie Mae meet or exceed those attained at the peak of the GFC while those for Freddie Mac are so far very subdued. There is another interesting question related to the split between private and Agency credit in this space. As risk has clearly risen in multifamily housing, can we expect the non-agency to step back? The Federal Reserve Financial Accounts of the US (also known as the Z.1 and formerly known as the Flow of Funds (FOF) or Mortgage Debt Outstanding (MDO)) provides an overview of this market on a quarterly basis. Holdings of credit risk in this space by class of investor may be viewed in the chart below: A number of interesting points stand out here. First, between the fourth quarters of 2012 and 2019, multi-family MDO surged by 79%, likely due to the need for affordability rental housing. This surge slowed considerably in the first two quarters of this year, but so far remains on an upward trajectory. A second observation is that the GSE share of the market grew by over 6% between the fourth quarters of 2015 and 2019 period, due to their strong position in the affordable space. Subsequently, this share has plateaued in the first two quarters of 2020. Over the period 2019 Q4-2020 Q2, banks lost 0.3% while insurance companies gained 0.6% share. So far, the Covid-19 crisis is slowing the growth in the market but the aggregate public/private share has not been materially impacted. No one knows the trajectory of residential housing over the next several years given the medical, financial, and policy uncertainties. In such an environment decision making needs to take into account a careful assessment of new and emerging trends that the new tools make possible. |

Archives

July 2024

Tags

All

|

RECURSION |

|

Copyright © 2022 Recursion, Co. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed