|

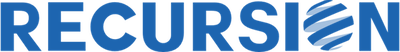

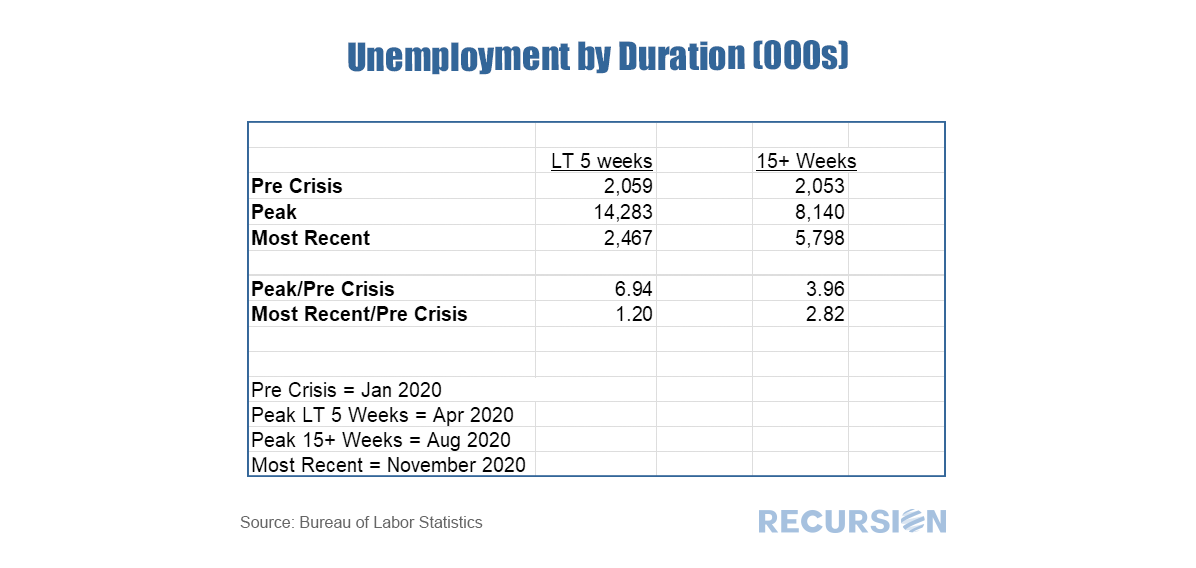

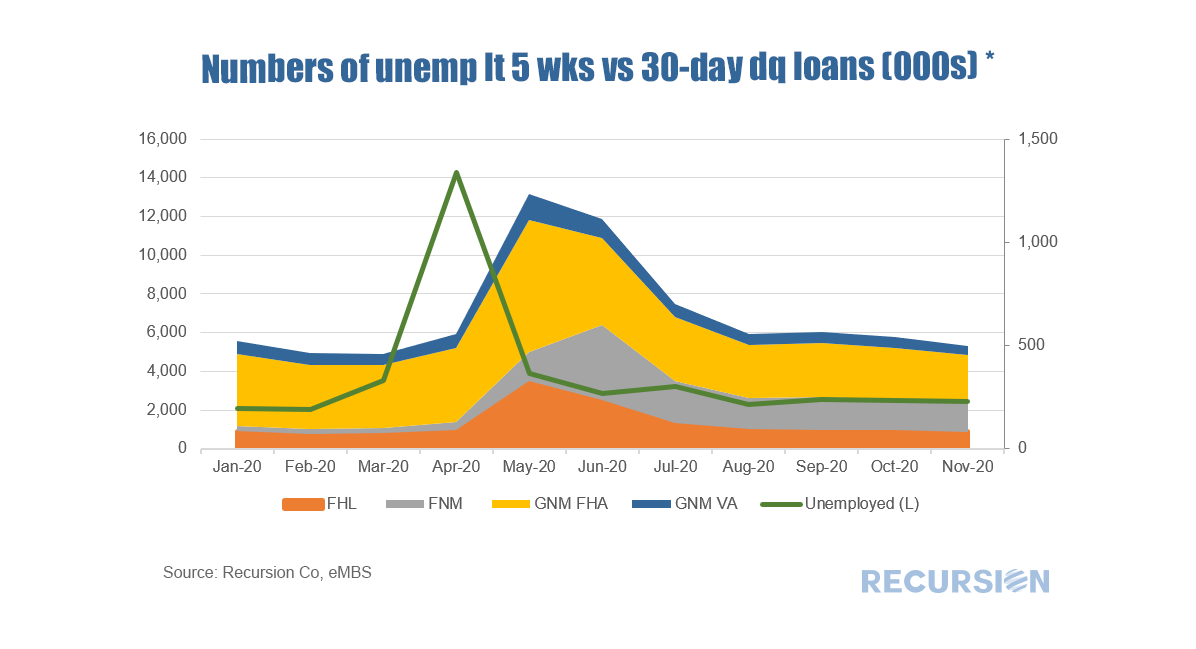

In prior posts, we have pointed out the tight relationship between unemployment and mortgage delinquency[1]. This note extends this analysis by looking at this relationship at particular durations. Every month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics releases data on the “Duration of Unemployment”[2]. For example, below find a table containing data for the number of unemployed people in before, during and after the shock associated with the onset of the Covid-19 crisis by how long they have been unemployed. In April there was a sharp spike in the number of newly unemployed people (less than 5 weeks) but this number dropped considerably as the economy re-opened. The number of longer-term unemployed (15 weeks and higher) peaked in August but has been declining only slowly since this time. This likely reflects workers in sectors, (tourism, retail, restaurants etc) that have yet to fully recover. On the idea that unemployment is the prime driver of delinquency we can plot the number of short-term unemployed against the number of loans that are 30 days delinquent, and the number of longer-term unemployed vs the number of loans that are 90+ days delinquent. The correlations are striking. The 30-day delinquency lags the number of short-term unemployed by a month or so. Both peaked in the Spring, then have subsequently returned to approximately pre-crisis levels. The number of longer-term unemployed and the number of loans 90+ days delinquent is both declining slowly, but the pace of decline in longer-term delinquency’s is slower than that in the number of unemployed. Another interesting observation is that the ratio of the number of longer-term unemployed people to the number of 90+ day delinquent loans is about 4.8:1 (5.8 million / 1.2 million). The size of this ratio may reflect the fact that many of the jobs lost are in the lower-wage service sector, so these workers are less likely to be homeowners. Another possibility is that some number of unemployed are in two-earner households that can make payments based on the income of a single earner. Looking forward, a key question is what will happen when forbearance expires. The rate of 90+ day delinquencies may be declining slower than the number of unemployed because some households are choosing to build cash reserves even if they can afford to make payments. Right now, the forbearance period will start to conclude for many households next spring, but continued-high Covid-19 counts may result in an extension. |

Archives

February 2024

Tags

All

|

RECURSION |

|

Copyright © 2022 Recursion, Co. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed